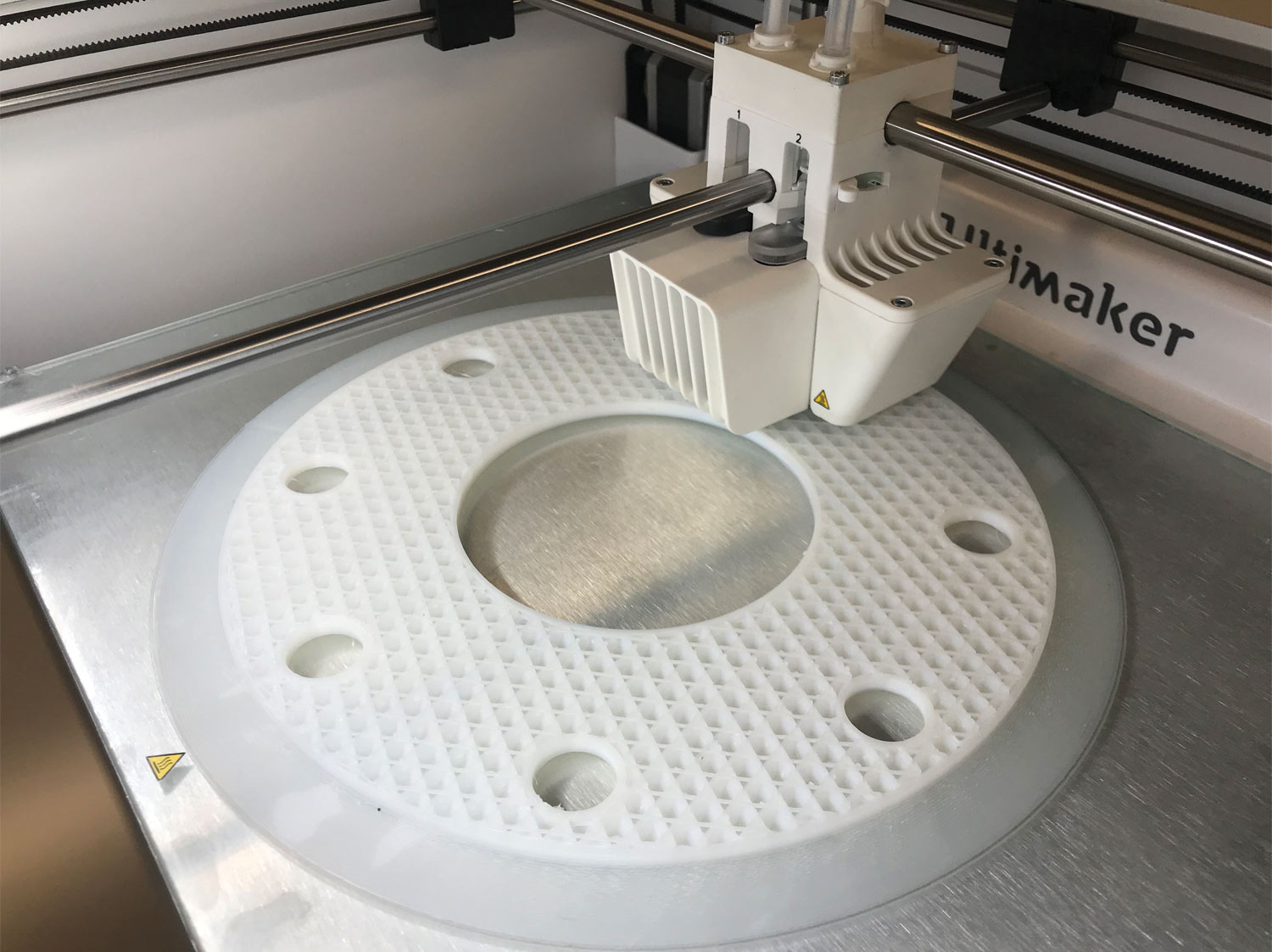

he material extrusion method of additive manufacturing using filaments, also known as fused filament fabrication (FFF), was patented in 1992. This method of 3D printing takes a thermoplastic feedstock in filament form, pushes it through a hot nozzle and deposits the melted plastic in a specified pattern layer-by-layer until the part is finished. FFF has gained popularity and rapid adoption due to the simplicity of the technology, availability of inexpensive printers and the ability to use a variety of polymers and polymer composites. Multiple colors or even different materials can be printed in the same part design. FFF is suitable for prototyping, jigs and fixtures, or for repairs where quick access to on-site replacement parts is desirable. Figure 1 shows an example of FFF printing.

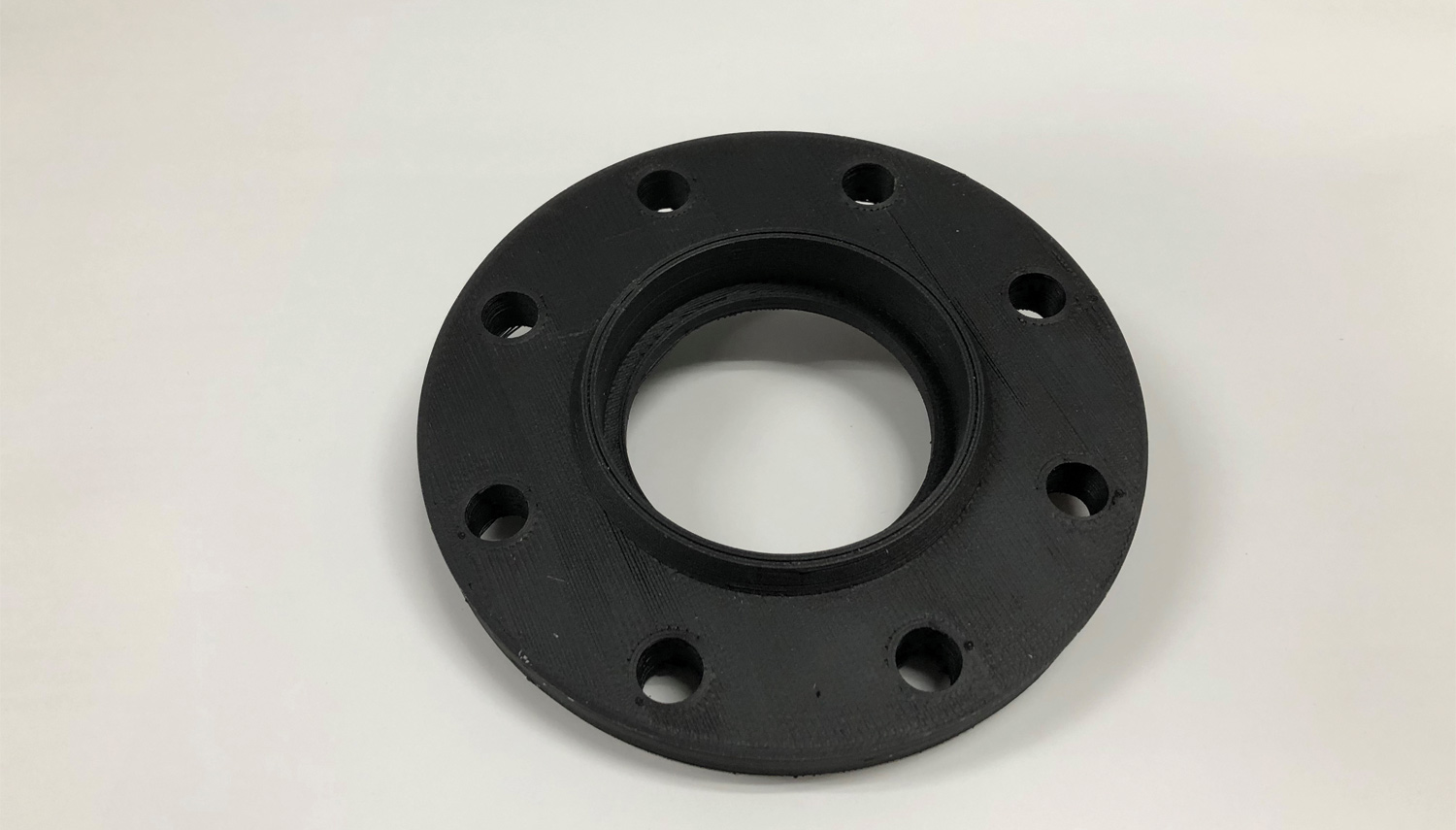

Figure 1: A common printing apparatus, seen here using PVDF filament to print an 8.5″ flange.

Materials used for FFF and other 3D printing technologies include polyamide 11, polyamide elastomers and fluoropolymers. A fluoropolymer family that shows promise for use in 3D printing is polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and PVDF copolymers with hexafluoropropylene (HFP). PVDF is considered an engineering fluoropolymer due to its unusually high tensile strength and modulus.

Attributes of PVDF polymers

PVDF is a semi-crystalline engineering fluoropolymer that can be adapted in many ways by copolymerization with HFP. Figures 2 and 3 show the monomers used to make PVDF homopolymer and PVDF copolymer. The standard PVDF homopolymer does not pick up moisture, is chemically resistant, has excellent flame resistance, outstanding UV, sunlight, abrasion resistance and radiation resistance. It is used in a range of final components and products such as tubing and piping systems, pump construction, tanks and vessels, membrane and filtration products and coatings. PVDF, unlike most other fluoropolymers, is a polymer with a wide temperature window between its melting point and upper processing temperature limit where it can be safely processed in 3D printing.

When PVDF is copolymerized it can maintain many of the same properties, such as temperature rating, weathering, flame resistance and chemical resistance properties, but the material gains ductility as it is made softer by the reduction in crystallinity.

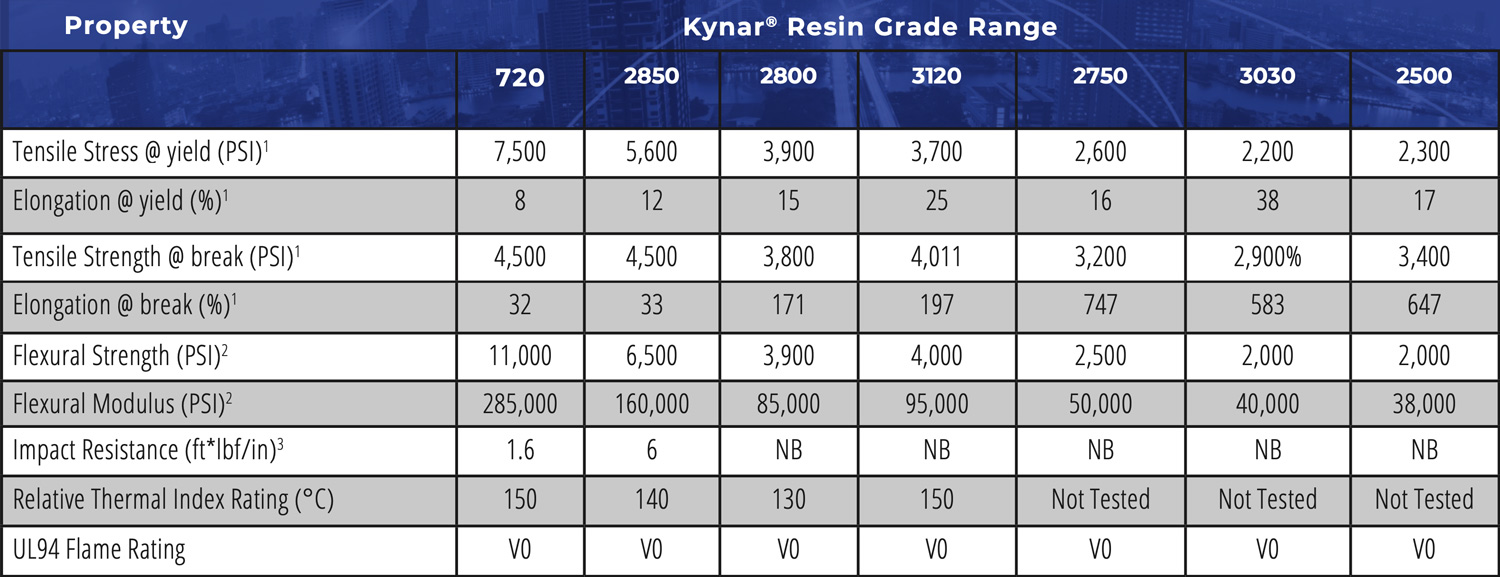

PVDF can be expected to be fully chemically resistant to solutions from pH below 1 up to 12 for continuous use and to pH 14 for occasional use. PVDF copolymer has an even broader pH range for continuous use, from much less than 1 up to 13.5. All forms of pure PVDF and PVDF copolymers have been studied in Florida 45-degree angle sunlight for long periods without loss of color or physical and mechanical properties. In addition, due to minimal moisture absorption and excellent UV and sunlight resistance, PVDF and PVDF copolymers may be stored indefinitely and do not need to be dried before 3D printing. Many grades of PVDF and PVDF copolymer have been tested for long-term thermal stability to UL® Relative Thermal Index (RTI) standard and some have a RTI temperature rating as high as 150C. Additionally, all grades of PVDF and PVDF copolymer are listed as UL94 V0 for flame resistance (see table 1). These are not grades specifically designed for 3D printing but are included to show the range of properties available in this fluoropolymer family. More specific grades for FFF printing are discussed below.

2ASTM D790 Type 1

3ASTM D256 1/8 inch bars

Table 1: Property ranges for all grades of Kynar® PVDF.

Printing with PVDF

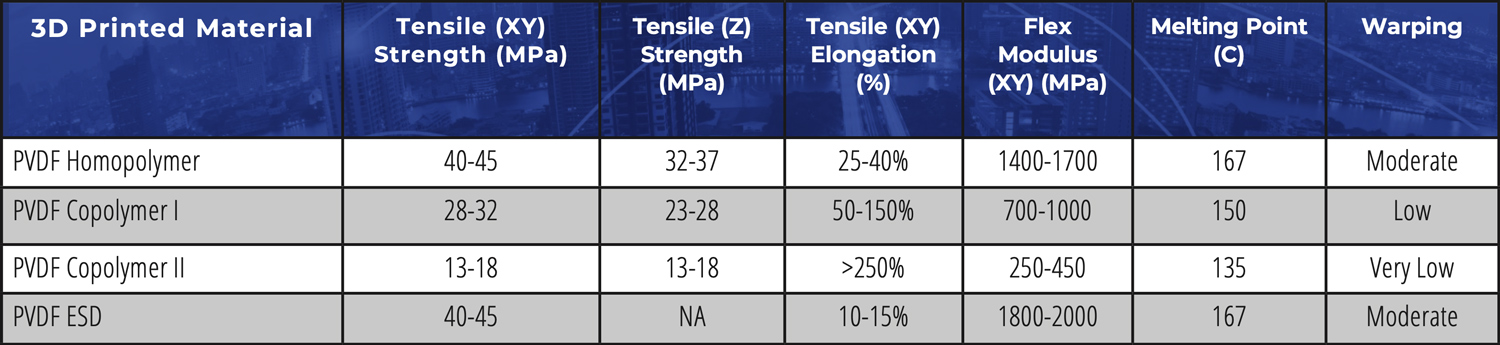

There are now filaments available with high flexibility copolymers, moderate flexibility copolymers and high stiffness homopolymers — depending on the mechanical properties required for your applications. All have good chemical resistance and UL94 V0 flame rating. These show strong layer-to-layer adhesion and can be printed with sparse infill all the way to 100 percent infill yielding > 99 percent dense parts depending on the application properties required. A unique feature is the ability to print without having to pre-dry the filaments as many other materials require.

These exciting properties open many different applications for the material in FFF printing. Parts can be printed for functional prototyping purposes, jigs and fixtures, or even for low volume on-demand production parts that allow for a more economical solution when a production environment is stopped due to a broken part. For example, to be injection molded, the part shown in Figure 5 would require a complex and expensive mold. By printing via FFF, users can reduce the cost and lead time for low volume parts. These advantages are especially important to address equipment failures that require immediate resolution, or where the end use takes place in a remote location such as an aircraft carrier at sea. This same thinking can apply to other industrial process equipment, such as flanges, valves and a myriad of other fittings in chemical processing environments, oilfield operations or other fast-paced industries where downtime due to a broken part results in costly situations that can be easily mitigated by FFF printing a replacement part from PVDF.

In addition, by optimizing the polymer composition and printing settings for PVDF 3D printing, you can use the strengths of PVDF to obtain highly dense, robust parts with great layer adhesion. The same property that makes PVDF not adhere to glass is what allows it to adhere to itself very well.

Good adhesion to the buildplate is critical to successfully printing any polymer. PVDF adheres best with PVA glue applied to a glass buildplate. Research has found that Elmer’s® Extra Strength glue sticks work very well with PVDF, but other more specialized adhesive solutions also work. Unlike most amorphous polymers, increasing buildplate temperatures does not decrease warping, as the polymer will still crystallize. A build plate temperature of around 158°F/70°C provides the best adhesion and least warping for most PVDF formulations. It is recommended to print PVDF with a brim or a raft to help prevent the corners of the part from peeling up as the part is printed.

PVDF can be printed on most commercially available 3D printers that can process ABS. The nozzle temperature used in PVDF printing range from 464°F/240°C to 518°F/270°C depending on the formulation being printed. A heated build chamber is not required to print PVDF, but an enclosure or regulated build environment may improve part-to-part consistency. Most PVDF formulations require some form of print cooling to resolve fine features. A cooling fan at 30 percent duty cycle works well, but this can vary drastically depending on the power of the print cooling fan. PVDF homopolymer formulations are able to print at higher speeds (50mm/s) than most copolymers and copolymer blends (30mm/s). Stiffer homopolymer and copolymers print well on both Bowden and direct drive extruders, but highly flexible copolymers work much better on direct drive printers.

Figure 6: Three parts that have been 3D printed from PVDF resins. The white is an unfilled PVDF and the black PVDF has a conductive filler.

PVDF formulations for FFF printing

Another challenge with FFF printing of PVDF is the lack of suitable support materials. Common soluble support materials, such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or breakaway support materials like ABS and PETG, don’t stick to PVDF well or lack the strength to counter PVDF’s shrinkage upon cooling. A new breakaway and solvent-soluble support material specifically for PVDF allows users to print larger, more complicated parts. The support material, used in printing a tee fitting, is the black material in figure 7.

Users can now produce high strength, high resolution parts, including parts that need electrostatic dissipation capabilities. For the highest strength, filaments based on homopolymer grades are preferred. For larger parts where high stiffness is not a need, filaments based on copolymer grades are preferred. Larger parts can also be printed using this material. An 8.5″ flange, seen in figure 8, is an example of what can be achieved.

Summary

The FFF process is well established with high quality printer suppliers and a network of filament specialists to serve the market.

Recent developments have made PVDF and PVDF copolymers more printable and offer users in the industrial or outdoor component an upgraded, but affordable, material in applications where increased chemical resistance, continuous thermal resistance up to 302°F/150°C for some grades, flame ratings and/or strong sunlight exposure are needed, for years of uninterrupted service.

PVDF has been studied specifically and several variations are available to meet typical applications or for special niche applications such as conductive materials, high strength composites and highly durable and ductile requirements.

Gene Alpin is a field sales engineer for the High Performance Polymers group at Arkema, covering fluoropolymer sales for the eastern United States. After graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemical engineering from Villanova in 2016, he joined Arkema and has held roles in marketing and sales. Alpin is a member of the Board of Directors for the Philadelphia Section of SPE.

Greg O’Brien is a polymer fellow and research and development manager for the Fluoropolymers division of Arkema Inc. He has worked in high performance polymers research and development for more than 35 years, with E.I. Dupont, ICI Advanced Materials and for the last 22 years with Arkema High Performance Polymers. He holds more than 20 patent applications over a broad range of polymer applications.

Steve Serpe is a market manager for Specialty Powders and 3D Printing in the High Performance Polymers group at Arkema. He has been at Arkema since 2013, holding multiple roles.

For more information, contact Arkema Inc. at 900 First Avenue, King of Prussia, PA 19406-1308 USA; phone (610) 420-4611 or (800) 596-2750, fax (610) 205-7497, eugene.alpin@arkema.com or www.kynar.com.